I've been teaching a class on intermediate macroeconomics this quarter. Increasingly, over the past twenty years or more, intermediate macro classes at UCLA (and in many other top schools), have focused almost exclusively on economic growth. That reflected a bias in the profession, initiated by Finn Kydland and Ed Prescott, who persuaded macroeconomists to use the Ramsey growth model as a paradigm for business cycle theory. According to this Real Business Cycle view of the world, we should think about consumption, investment and employment 'as if' they were the optimal choices of a single representative agent with super human perception of the probabilities of future events.

Although there were benefits to thinking more rigorously about inter-temporal choice, the RBC program as a whole led several generations of the brightest minds in the profession to stop thinking about the problem of economic fluctuations and to focus instead on economic growth. Kydland and Prescott assumed that labor is a commodity like any other and that any worker can quickly find a job at the market wage. In my view, the introduction of the shared belief that the labor market clears in every period, was a huge misstep for the science of macroeconomics that will take a long time to correct.

In my intermediate macroeconomics class, I am teaching business cycle theory from the perspective of Keynesian macroeconomics but I am grounding old Keynesian concepts in the theory of labor market search, based on my recent books (2010a, 2010b) and articles (2011, 2012, 2013a, 2013b). I am going to use this blog to explain some insights that undergraduates can easily absorb that are adapted from my understanding of Keynes' General Theory. Today's post is about measuring employment. In later posts, I will take up the challenge of constructing a theory to explain unemployment.

Ever since Robert Lucas introduced the idea of continuous labor market clearing, the idea that it may be useful to talk of something called 'involuntary unemployment' has been scoffed at by the academic chattering classes. It's time to fight back. The concept of 'involuntary unemployment' does not describe a loose notion that characterizes the sloppy work of heterodox economists from the dark side. It is a useful category that describes a group of workers who have difficulty finding jobs at existing market prices.

The idea that the labor market is well described by a model in which a market wage adjusts to equate the quantity of labor demanded with the quantity supplied bears little resemblance to anything we see in the real world. What makes me so confident of that claim?

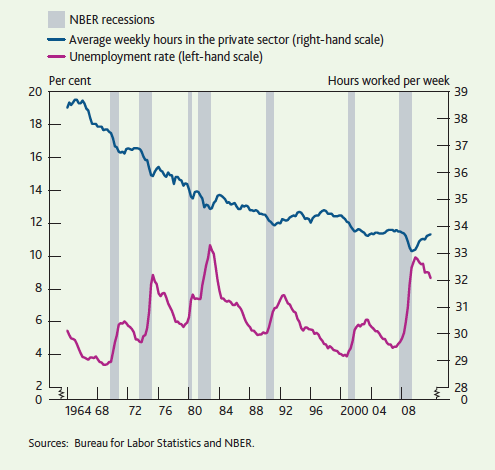

Employment varies over time for three reasons. First, the average number of hours fluctuates. Second people enter and leave the labor force and third, those people who are in the labor force flow into and out of unemployment. Figure 1 (taken from my 2013 Bank of England article) plots data from 1964 through 2012 on average weekly hours and the unemployment rate. The blue line, measured on the right scale, is average weekly hours. The pink line, on the left scale, is the unemployment rate. The grey shaded areas are NBER recessions.

The facts are clear. Although hours do fall during recessions, the movements in hours are swamped by movements in the unemployment rate. Consider, for example, the 2008 recession. Average weekly hours fell from 34 to 33. The unemployment rate, in contrast, increased from 4% to 10%.

The main story in the data on average weekly hours is that they declined from 39 hours per week in 1964 to 34 hours per week in 2012. As American workers got richer they collectively chose to take a larger share of their wages in the form of leisure. These movements are important if our goal is to understand long term trends: they do not tell us much about recessions.

What about the participation rate? Recently, there has been a great deal of angst amongst policy makers who are asking if the fall in the participation rate that occurred during the 2008 recession was cyclical or structural. Figure 2 sheds some light on that question. The graph demonstrates that there is no clear tendency for participation rates to drop in recessions. For example, participation was higher at the end of the 1973 recession than at the beginning and in a number of other post-war recessions it has remained flat. As with average weekly hours, this figure shows that movements in hours during recessions are almost entirely caused by movements in the unemployment rate.

So what does cause the participation rate to vary over time? I look at Figure 2 and I see a parabola. Participation went up from 1960 to 2000 as women entered the labor force. It started to fall again in 2000 as the baby boomer generation began to retire. These secular trends swamp business cycle movements in the participation rate and they are largely explained by sociology and by demographics.

Although there were benefits to thinking more rigorously about inter-temporal choice, the RBC program as a whole led several generations of the brightest minds in the profession to stop thinking about the problem of economic fluctuations and to focus instead on economic growth. Kydland and Prescott assumed that labor is a commodity like any other and that any worker can quickly find a job at the market wage. In my view, the introduction of the shared belief that the labor market clears in every period, was a huge misstep for the science of macroeconomics that will take a long time to correct.

In my intermediate macroeconomics class, I am teaching business cycle theory from the perspective of Keynesian macroeconomics but I am grounding old Keynesian concepts in the theory of labor market search, based on my recent books (2010a, 2010b) and articles (2011, 2012, 2013a, 2013b). I am going to use this blog to explain some insights that undergraduates can easily absorb that are adapted from my understanding of Keynes' General Theory. Today's post is about measuring employment. In later posts, I will take up the challenge of constructing a theory to explain unemployment.

Ever since Robert Lucas introduced the idea of continuous labor market clearing, the idea that it may be useful to talk of something called 'involuntary unemployment' has been scoffed at by the academic chattering classes. It's time to fight back. The concept of 'involuntary unemployment' does not describe a loose notion that characterizes the sloppy work of heterodox economists from the dark side. It is a useful category that describes a group of workers who have difficulty finding jobs at existing market prices.

The idea that the labor market is well described by a model in which a market wage adjusts to equate the quantity of labor demanded with the quantity supplied bears little resemblance to anything we see in the real world. What makes me so confident of that claim?

|

| Figure 1: Average Weekly Hours and the Unemployment Rate (c) Roger E. A. Farmer |

Employment varies over time for three reasons. First, the average number of hours fluctuates. Second people enter and leave the labor force and third, those people who are in the labor force flow into and out of unemployment. Figure 1 (taken from my 2013 Bank of England article) plots data from 1964 through 2012 on average weekly hours and the unemployment rate. The blue line, measured on the right scale, is average weekly hours. The pink line, on the left scale, is the unemployment rate. The grey shaded areas are NBER recessions.

The facts are clear. Although hours do fall during recessions, the movements in hours are swamped by movements in the unemployment rate. Consider, for example, the 2008 recession. Average weekly hours fell from 34 to 33. The unemployment rate, in contrast, increased from 4% to 10%.

The main story in the data on average weekly hours is that they declined from 39 hours per week in 1964 to 34 hours per week in 2012. As American workers got richer they collectively chose to take a larger share of their wages in the form of leisure. These movements are important if our goal is to understand long term trends: they do not tell us much about recessions.

What about the participation rate? Recently, there has been a great deal of angst amongst policy makers who are asking if the fall in the participation rate that occurred during the 2008 recession was cyclical or structural. Figure 2 sheds some light on that question. The graph demonstrates that there is no clear tendency for participation rates to drop in recessions. For example, participation was higher at the end of the 1973 recession than at the beginning and in a number of other post-war recessions it has remained flat. As with average weekly hours, this figure shows that movements in hours during recessions are almost entirely caused by movements in the unemployment rate.

|

| Figure 2: Participation and the Unemployment Rate (c) Roger E. A. Farmer |

What do I take away from these data? There are three reasons why employment fluctuates over time. People vary the average number of hours worked per week. Households send more or less members to look for a job. And those people looking for jobs find it more or less difficult to find one. The first two reasons for fluctuating employment could perhaps be modeled as the smooth functioning of a market in which the demand and supply of labor respond to changes in market prices. I cannot see any simple way to model unemployment fluctuations as the operation of a competitive market for labor in the usual sense in which economists use that term.

Repeat after me: the quantity of labor demanded is not always equal to the quantity supplied.