Like most academics, I spend much of my time asking for money from research councils. So, it is a welcome change for me to sit on the other side of the table in my role on the management team of Rebuilding Macroeconomics. This is an initiative located at the National Institute of Economic and Social Research in the UK and funded by the Economic and Social Research Council. Our remit is to act as gatekeepers to distribute approximately £2.4 million over the next four years to projects that have the potential to transform macroeconomics back to a truly policy relevant social science. We are seeking risky projects that combine insights from different disciplines that would not normally be funded and we expect that not all of them will succeed. It is our hope that one or more of the projects we fund will lead to academic advances and new solutions to the pressing policy issues of our time.

In addition to my role on the management team of Rebuilding Macroeconomics, I am Research Director at NIESR. I have already learnt a great deal from discussions with the other members of the team. The committee consists of myself, Angus Armstrong, of Lloyds Bank, Laura Bear of LSE, Doyne Farmer, of Oxford University, and David Tuckett, of UCL. Laura is a Professor of Anthropology who has worked extensively on the anthropology of the urban economy and she brings a refreshing perspective to the sometimes-insular world of economics. Doyne Farmer, no relation, is a complexity theorist who runs the INET Complexity Economics Centre at the Oxford Martin School. Doyne was trained as a physicist and he has a long association with the Santa Fe Institute in New Mexico. And last, but by no means least, David Tuckett is a psychologist at University College London where he directs the UCL Centre for the Study of Decision Making Under Uncertainty. As you might imagine, conversations among this diverse group have been eye-opening for all of us.

We have chosen to allocate funds by identifying a number of ‘hubs’ that are loosely based around a set of pressing public issues. So far, we have identified three: 1) Can globalisation benefit all? 2) Why are economies unstable? and 3) Do we have confidence in economic institutions? In this post, I want to focus on the third of these questions which evolved from conversations between those of us on the management team and that Laura and I have spent quite a bit of time refining.

We can break institutions into two broad groups: Academic institutions that shape the culture of economists. And government and policy institutions that transmit this culture to the wider public sphere. Research on academic institutions involves the organisation of economic education in universities, the journal structure, the rules for promotion and tenure in academic departments and the socialisation and seminar culture of the tribe of the Econ. Research on policy making institutions like the Bank of England, the Treasury and the IMF involves the way that insular thinking, learned in graduate schools, is transmitted to society at large.

Insular thinking is reflected, for example, in economic journal publishing, a process that is highly centralised around five leading journals. These are the American Economic Review, the Quarterly Journal of Economics, the Review of Economic Studies, Econometrica and the Journal of Political Economy. For a young newly appointed lecturer, publishing a paper in one of these top five journals is a pre-requisite for promotion in a leading economic department in the United States, the United Kingdom and many of the top Continental European departments. This process is more often than not depressingly slow. Even for a well-established leading economist, publication in a top five journal is never guaranteed. And when a paper is finally published, it is after rejection from three or more other journals and the collective efforts of a coterie of referees. This experience, as I learned from Doyne, is not characteristic of the natural sciences.

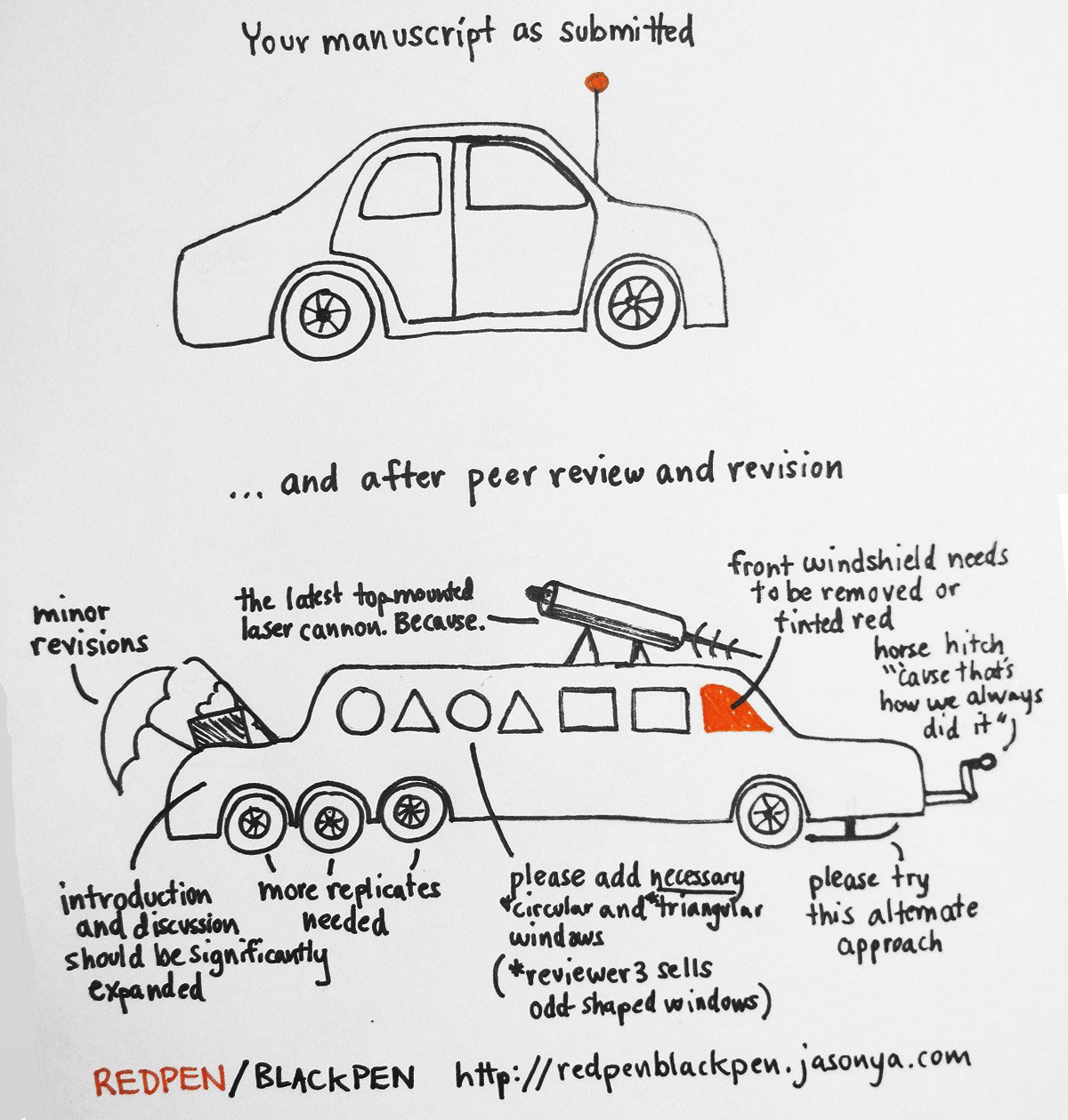

From Redpen/Blackpen twitter feed

In economics, the expected time from writing a working paper to publication in a journal is around four years. That assumes that the researcher is shooting for a top journal and is prepared to accept several rejections along the way. When a paper is finally accepted it must, more often than not, be extensively rewritten to meet the proclivities of the referees. In my experience, not all of the referee reports lead to improvements. Sometimes, the input of dedicated referees can improve the final product. At other times, referee comments lead to monstrous additions as the editor incorporates the inconsistent approaches of referees with conflicting views of what the paper is about.

It is not like that in other disciplines. I will paraphrase from my memory of a conversation with Doyne, so if you are a physicist or a biologist with new information, please feel free to let me know in the comment section of this blog. In physics, a researcher is rightfully upset if she does not receive feedback within a month. And that feedback involves short comments and an up or down decision. In physics, there is far less of a hierarchy of journals. Publications are swift and many journals have equal weight in promotion and tenure decisions.

I do not know why economics and physics are so different but I suspect that it is related to the fact that economics is not an experimental science. In macroeconomics, in particular, there are often many competing explanations for the same limited facts and it would be destructive to progress if every newly minted graduate student were to propose their own new theory to explain those facts. Instead, internal discipline is maintained by a priestly caste who monitor what can and cannot be published.

The internal discipline of macroeconomics enables most of us to engage in what Thomas Kuhn calls ‘normal science’. But occasionally there are large events like the Great Depression of the 1930’s, the Great Stagflation of the 1970’s or the Great Recession of 2008, that cause us to re-evaluate our preconceived ideas. A journal culture that works well in normal times can, in periods of revolution, become deeply suppressive and destructive of creative thought. Now would be a very good time to re-evaluate our culture and perhaps, just perhaps, we can learn something from physics.