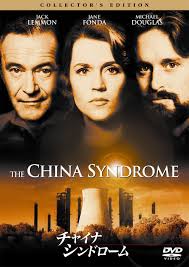

I feel a little like Rip Van-Winkle. The consensus amongst economists in the 1980s was that trade is always and everywhere good for everyone. After attending a UCLA workshop on trade a couple of weeks ago, I learned that all that has changed. There is a new consensus, summarized in two papers, "The China Syndrome", published in the American Economic Review, and "the China Shock", a new working paper, by David Autor, David Dorn and Gordon Hanson (ADH). According to their research, the effects of trade with China have been truly catastrophic for the average American worker. Over to ADH --

Our analysis finds that exposure to Chinese import competition affects local labor markets not just through manufacturing employment, which unsurprisingly is adversely affected, but also along numerous other margins. Import shocks trigger a decline in wages that is primarily observed outside of the manufacturing sector.

Sound familiar? This is a case of academic economists catching up with what the median blue-collar worker has known for a long time. The U.S. lost jobs to China and the average American worker was not compensated by the winners. And there were winners.

China's economic growth has lifted hundreds of millions of individuals out of poverty. The resulting positive impacts on the material well-being of Chinese citizens are abundantly evident. Beijing's seven ring roads, Shanghai's sparkling skyline, and Guangzhou's multitude of export factories none of which existed in 1980 are testimony to China's success.

Nor were the winners only Chinese workers. If your income is primarily generated by ownership of human or physical capital; you have benefited enormously from the chance to combine your talents, in the case of human capital, and your wealth, in the case of physical capital, with a vast pool of unskilled labor. But those benefits were never passed on to American workers and American workers are now voicing their collective displeasure at the ballot box.