"In economics, the majority is always wrong." — John Kenneth Galbraith

Asset Prices in a Lifecycle Economy

I have just completed a new paper on asset prices, "Asset Prices in a Lifecycle Economy". The paper is available here from the NBER or here from my website. This is a good time to comment on asset price volatility and the apparently contradictory findings of two of the 2013 Nobel Laureates because my paper sheds light on this issue.

In 2013, Gene Fama, Lars Hansen and Robert Shiller, shared the Nobel Prize for their empirical analysis of asset prices.1

Fama won the Nobel Prize for showing that financial markets are efficient. He meant, that it is not possible to make money by trading financial assets because markets already incorporate all available information.

Shiller won the Nobel Prize for showing that financial markets are inefficient. He meant that the ratio of the price of a stock to the dividends it earns, returns to a long run average value; hence, an investor can profit by holding undervalued stocks for very long periods.

These apparently contradictory results are consistent because Fama and Shiller are referring to different concepts of efficiency.

Financial markets are like insurance markets. If you own a house you will insure the house against fire. And since not all houses burn down at the same time, the premiums we all pay for fire insurance can be used to compensate the unlucky few who suffer from a loss in any given year. But to benefit from insurance, you must purchase the insurance before your house burns down.

Oreopolous and coauthors have shown that people who start their working life in a recession are worse off for their entire lives than people born in a boom. Given the opportunity, we would all choose to purchase insurance over the state of the world into which we are born, for the same reason that we buy fire insurance on our house. I call our inability to purchase this insurance, the absence of prenatal financial markets. It is the inability of the young to trade in prenatal financial markets that explains why the financial markets are not Pareto Optimal.

In my model, huge inefficient asset price fluctuations occur because the unborn are not around to profit from them. Risky assets trade at a premium because retirees have no other source of income and cannot afford to gamble away their savings. If our children's children's children could trade in the markets, they would short stocks that are overvalued, and buy those that are undervalued. But for those of us with finite horizons, life is too short to make those trades. As Keynes quipped; Markets can remain irrational for longer than you or I can remain solvent.

When Fama says that financial markets are efficient, he means informational efficiency. There is a second concept that economists call Pareto efficiency. This means that there is no possible intervention by government that can improve the welfare of one person without making someone else worse off. The fact that markets are informationally efficient does not necessarily mean that they are Pareto efficient and that fact helps to explain why financial markets appear to do such crazy things over short periods of time.

Long-run predictability is not the only feature of asset prices that is hard to understand. Economists also have a hard time explaining why asset prices are so volatile (the excess volatility puzzle) and why the return to equity has historically been six percentage points higher than the return to holding government debt, (the equity premium puzzle).

My new working paper explains both these asset pricing puzzles. I don't need to assume that there are financial frictions, sticky prices or irrational behavior. The only thing that is different about my work from standard macroeconomic models is birth and death. Rather than assume, as do many models, that there is a single representative agent in the world, I assume instead that people are born, they work, they retire and they die.

|

| Figure 1 Source "Asset prices in a Lifecycle Economy", (c) Roger E. A. Farmer |

Figure 1 compares simulated data from my model (left panel) with US data (right panel). The blue line in both cases is the safe rate of return and the green line is the stock market return.

In the simulated data, like the actual data, the stock market is risky with a higher average return than a safe short asset. What explains my results?

Financial markets are like insurance markets. If you own a house you will insure the house against fire. And since not all houses burn down at the same time, the premiums we all pay for fire insurance can be used to compensate the unlucky few who suffer from a loss in any given year. But to benefit from insurance, you must purchase the insurance before your house burns down.

Oreopolous and coauthors have shown that people who start their working life in a recession are worse off for their entire lives than people born in a boom. Given the opportunity, we would all choose to purchase insurance over the state of the world into which we are born, for the same reason that we buy fire insurance on our house. I call our inability to purchase this insurance, the absence of prenatal financial markets. It is the inability of the young to trade in prenatal financial markets that explains why the financial markets are not Pareto Optimal.

In my model, huge inefficient asset price fluctuations occur because the unborn are not around to profit from them. Risky assets trade at a premium because retirees have no other source of income and cannot afford to gamble away their savings. If our children's children's children could trade in the markets, they would short stocks that are overvalued, and buy those that are undervalued. But for those of us with finite horizons, life is too short to make those trades. As Keynes quipped; Markets can remain irrational for longer than you or I can remain solvent.

__________________________________________________

1. Lars Hansen won for his work on estimation and I will not have a lot here to say about his contribution. It has already become a part of the curriculum for every Ph.D. student in economics.

Doing Economics: A Thought for the Day for Grad Students

A common mistake amongst Ph.D. students is to place too much weight on the ability of mathematics to solve an economic problem. They take a model off the shelf and add a new twist. A model that began as an elegant piece of machinery designed to illustrate a particular economic issue, goes through five or six amendments from one paper to the next. By the time it reaches the n'th iteration it looks like a dog designed by committee.

Mathematics doesn't solve economic problems. Economists solve economic problems. My advice: never formalize a problem with mathematics until you have already figured out the probable answer. Then write a model that formalizes your intuition and beat the mathematics into submission. That last part is where the fun begins because the language of mathematics forces you to make your intuition clear. Sometimes it turns out to be right. Sometimes you will realize your initial guess was mistaken. Always, it is a learning process.

Mathematics doesn't solve economic problems. Economists solve economic problems. My advice: never formalize a problem with mathematics until you have already figured out the probable answer. Then write a model that formalizes your intuition and beat the mathematics into submission. That last part is where the fun begins because the language of mathematics forces you to make your intuition clear. Sometimes it turns out to be right. Sometimes you will realize your initial guess was mistaken. Always, it is a learning process.

Did Keynes have a Theory of Aggregate Supply?

My old classmate Nick Rowe has a new post on Chapter 3 of The General Theory. In Nick's words,

Back to Nick...

Start with three equations.

1. The production function: Y=F(L). Output (Y) is a function of employment (L).

2. A "classical" labour demand curve: W/P=MPL(L). The real wage (W/P) equals the Marginal Product of Labour, which is a decreasing function of employment. This is Keynes' "first classical postulate", which he agreed with.

3. A "classical" labour supply curve: W/P=MRS(L,Y). The real wage equals the Marginal Rate of Substitution between labour (or leisure) and output (or consumption). This is Keynes' "second classical postulate", which he disagreed with (except at "full employment").

From 1 and 2, plus some tedious math, we can derive what Keynes calls "the aggregate supply function": PY/W = S(L). It shows the value of output, measured in wage units, as a function of employment. It is substantively identical to the Short Run Aggregate Supply Curve in intermediate macro textbooks that assume sticky nominal wages: Y=H(P/W), which uses the exact same equations 1 and 2, but presents the same solution differently.

From 1 and 3, plus some tedious math, we can derive a second "aggregate supply function", that is not in the General Theory: PY/W = Z(L). It is substantively identical to the short run aggregate supply curve implicit in New Keynesian models, which assume sticky P and perfectly flexible W, so the economy is always on the labour supply curve and always on the production function.

From 1 and 2 and 3, plus some tedious math, we can solve for Y, L, and W/P, and derive a third aggregate supply function: Y=Y*. This is the textbook Long Run Aggregate Supply curve. It is identical to the solution we could get if we solved for the levels of Y, L, and W/P that satisfied both the first and second "aggregate supply functions".

Nick's first supply curve is the only supply curve in The General Theory. All else is due to misinterpretations by later economists who tried to make sense of what Keynes really meant (ineffectively in my view). We don't need sticky prices (supply curve number 2) and we don't need to reintroduce the second classical postulate through the back door (supply curve number 3). That is 1950s MIT talking and it led us down the wrong path.

In Chapter 4 of The General Theory, Keynes suggests that we measure output in wage units. Here is Nick again on that point...

And Nick claims later in his post that

In Chapter 4 of The General Theory, Keynes suggests that we measure output in wage units. Here is Nick again on that point...

Keynes' weird habit of measuring output in wage units had an unfortunate result: because [it implies that] doubling the real wage, for a given level of output and real income, would exactly double output demanded.That is simply false. There is no unique concept of output in a multi-good economy. Contrary to Nick's assertion, there is nothing 'weird' at all about the measurement of GDP in wage units. It is a clever device that allows us to measure real GDP and to concentrate on the determinants of aggregate economic activity.

And Nick claims later in his post that

There is absolutely nothing new on the supply-side in chapter 3 of the General Theory.Not so. Although there is no 'theory' of aggregate supply that would satisfy a micro economist, that is not the same as Nick's claim that there is nothing new. What is new is the assertion that Keynes will drop the classical second postulate. In other words: throw away the labor supply curve. Making sense of that statement is what my own work is all about.

Back to Nick...

It is the demand-side that is new. It is the idea that the demand for goods is a function of the quantity of labour that households are actually ableto sell. If households are rationed in the labour market, that will spillover and affect their demand in the output market. Because the amount of labour they are actually able to sell, and hence the income they will earn from wages plus non-wages, depends on demand. Which means that demand depends upon demand. Demand depends on itself. That was new, and interesting."

I agree that the consumption function, the idea that "demand depends on itself", was a central element of the theory of The General Theory. But is there a Keynesian consumption function in the data? I don't think so. At least, not in the form that Keynes postulated in the GT.

Attempts to reconcile short run cross section evidence and long run time series evidence on the value of the multiplier led to permanent income theory and the Ricardian equivalence debate. That debate is what we are all so heated up over right now. If the GT is nothing but the Keynesian multiplier, and if that theory is wrong, then what is the Wannabe Keynesian left with?

Attempts to reconcile short run cross section evidence and long run time series evidence on the value of the multiplier led to permanent income theory and the Ricardian equivalence debate. That debate is what we are all so heated up over right now. If the GT is nothing but the Keynesian multiplier, and if that theory is wrong, then what is the Wannabe Keynesian left with?

The Wannabe Keynesian is left with the theory of supply; a denial of the classical second postulate. My work builds a cohesive microeconomic foundation to the economics of Keynes' theory of aggregate supply. That foundation denies Say's law, (the proposition that supply creates its own demand) and it allows us to us refocus the debate on where it belongs. What is the best way to restore effective demand?

My Quiz for Wannabe Keynesians

Simon Wren-Lewis has a great post today on what makes a Keynesian. Here is my answer together with a quiz for wannabe Keynesians.

Figure 1 is a picture that goes by the name of the Keynesian cross. On the horizontal axis is income; the value of all wages, rents and profits earned from producing goods and services in a given year. On the vertical axis is planned expenditure; the value of all spending on goods and services produced in the economy in a given year. Since this is a closed economy, all expenditure is allocated to one of three categories; expenditure on consumption goods, expenditure on investment goods and government purchases. Since every dollar spent must generate income for someone; in a Keynesian equilibrium, income must equal planned expenditure.

The upward sloping green line, at 45 degrees to the origin, is the Keynesian aggregate supply curve. This green line is the Keynesian theory of aggregate supply. It says that whatever is demanded will be supplied.

The upward sloping red line is the Keynesian theory of aggregate demand. In its simplest form, G and I, represent exogenous spending by government and by investors. The idea that investment is exogenous, was Keynes' way of closing the system. He thought that investment is driven by the animal spirits of investors.

The Keynesian model says, that in equilibrium, the economy will come to rest at a point where the green line and the red line cross. There is no necessary reason why that point should be associated with full employment, and most of the time, it won't be: Hence, the title of Keynes' book, the General Theory of Employment Interest and Money.

The jewel in the crown of Keynesian theory is the consumption function, represented by the equation,

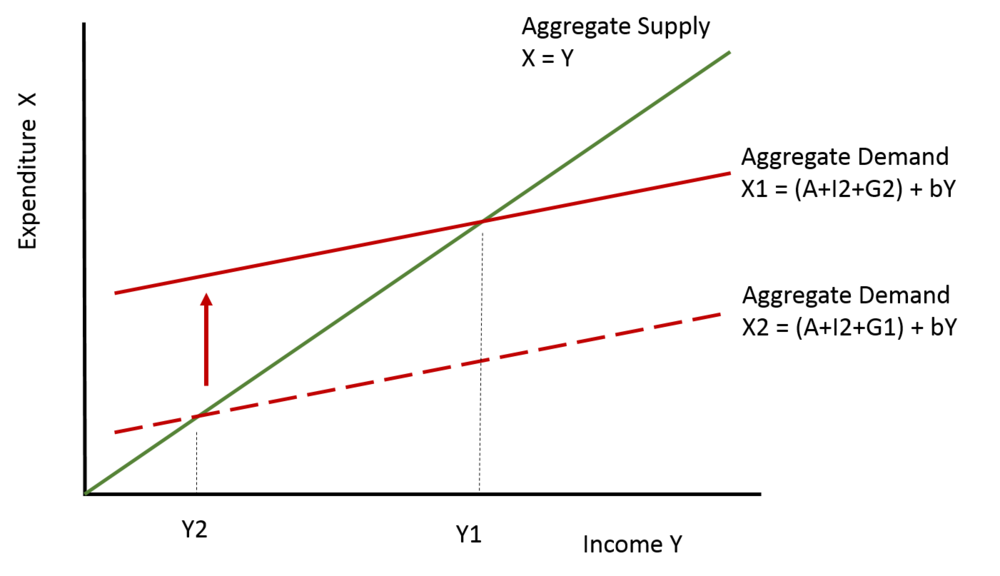

Figure 2 is the Keynesian explanation for the Great Depression. The top red line, labelled X1, represents expenditure in 1929 before the stock market crash. Government purchases were equal to G and investment was equal to I1.

The lower red line, labelled X2, represents expenditure in 1932, after the stock market crash. Government purchases were still equal to G, but investment fell from I1 to I2. This shifted down the Keynesian aggregate demand curve and led to a drop in income that was bigger than the original drop in I. Expenditure, equal to income, came to rest at point Y2. The fall in Y was bigger than the fall in I because, as investment fell, so consumption also fell. And every one dollar of reduced consumption led to an additional drop in income of b dollars. That at least is the theory.

First, let me delve into a little highbrow theory.

|

| Figure 1: The Keynesian Cross |

Figure 1 is a picture that goes by the name of the Keynesian cross. On the horizontal axis is income; the value of all wages, rents and profits earned from producing goods and services in a given year. On the vertical axis is planned expenditure; the value of all spending on goods and services produced in the economy in a given year. Since this is a closed economy, all expenditure is allocated to one of three categories; expenditure on consumption goods, expenditure on investment goods and government purchases. Since every dollar spent must generate income for someone; in a Keynesian equilibrium, income must equal planned expenditure.

The upward sloping green line, at 45 degrees to the origin, is the Keynesian aggregate supply curve. This green line is the Keynesian theory of aggregate supply. It says that whatever is demanded will be supplied.

The upward sloping red line is the Keynesian theory of aggregate demand. In its simplest form, G and I, represent exogenous spending by government and by investors. The idea that investment is exogenous, was Keynes' way of closing the system. He thought that investment is driven by the animal spirits of investors.

The Keynesian model says, that in equilibrium, the economy will come to rest at a point where the green line and the red line cross. There is no necessary reason why that point should be associated with full employment, and most of the time, it won't be: Hence, the title of Keynes' book, the General Theory of Employment Interest and Money.

The jewel in the crown of Keynesian theory is the consumption function, represented by the equation,

C = A + bY,

where A is autonomous consumption spending (this is a constant) and b is the marginal propensity to consume (this is a number between zero and one).

|

| Figure 2: The Great Depression |

The lower red line, labelled X2, represents expenditure in 1932, after the stock market crash. Government purchases were still equal to G, but investment fell from I1 to I2. This shifted down the Keynesian aggregate demand curve and led to a drop in income that was bigger than the original drop in I. Expenditure, equal to income, came to rest at point Y2. The fall in Y was bigger than the fall in I because, as investment fell, so consumption also fell. And every one dollar of reduced consumption led to an additional drop in income of b dollars. That at least is the theory.

Keynes' remedy? Government must spend to replace the lost investment spending.

|

| Figure 3: The Keynesian Remedy |

Figure 3 shows how that is supposed to work. The lower dashed red line is aggregate demand in 1932 in the depth of the Depression. Government purchases did not change much during the 1930s, but as the world entered WWII, government purchases in the U.S. increased from 15% of the economy to 50% in the space of three years. As G increased from G1 to G2, the dashed red line on Figure3 shifted up and expenditure went from X2 back up to X1. Notice that G2 + I2 on Figure 3 equals I1 + G on Figure 2.

The increase in the size of government in war time was huge and was enough to restore full employment at Y1; but now the spending that had been carried out in 1929 by the private sector was carried out in 1943 by the government. We cured the unemployment problem by putting all of those unemployed people in the army.

It is also worth pointing out that private consumption expenditure fell during WWII. Keynesian theory predicts that it should have increased. That fact is a bit uncomfortable for textbook Keynesians who appeal to the special circumstances of a wartime economy. Here's Tyler Cowen's take on that debate.

The increase in the size of government in war time was huge and was enough to restore full employment at Y1; but now the spending that had been carried out in 1929 by the private sector was carried out in 1943 by the government. We cured the unemployment problem by putting all of those unemployed people in the army.

It is also worth pointing out that private consumption expenditure fell during WWII. Keynesian theory predicts that it should have increased. That fact is a bit uncomfortable for textbook Keynesians who appeal to the special circumstances of a wartime economy. Here's Tyler Cowen's take on that debate.

OK: enough theory. Here is My Quiz for Wannabe Keynesians.

1: Does demand determine employment? Is the 45 degree line an aggregate supply curve? And if you answered yes to this question: Is the 45 degree line a theory of aggregate supply in the short run, or in the long run?

2: Does you answer to (1) depend on the assumption that prices are sticky?

3: Is the Keynesian consumption function a good way to think about aggregate demand? Does consumption depend on income, and if so, what is the value of the marginal propensity to consume?

If you answered YES to all three questions, you are a bonafide card carrying Keynesian of the New York Times variety.

Here are: My answers to My Quiz for Wannabe Keynesians

1). YES. The 45 degree line is an aggregate supply curve. Further, it is a LONG RUN aggregate supply curve. Forget about a vertical Phillips curve. It simply is not there in the data.

2). NO. The fact that anything demanded will be supplied has absolutely nothing to do with sticky prices or wages. I repeat; the 45 degree line is a LONG RUN aggregate supply curve. Prices and wages are determined by monetary factors and by beliefs and there is little or no evidence that they adjust to clear markets as classical theorists would tell us.

3). NO. The Keynesian theory of consumption is not a good theory of aggregate demand. The evidence for a large multiplier is weak or non existent. I am perfectly willing to be proved wrong on that point; but I have kept up with all of the available evidence (nicely summarized here by James Hanley) and I do not find it convincing.

Valery Ramey's work suggests that the multiplier, if anything, is slightly less than 1 and she finds that

Am I a Keynesian? I believe I am; but you can judge for yourself. My work explains (1). I am skeptical about (2) because the evidence suggests no stable connection between unemployment and inflation. In my view ANY combination of unemployment and inflation can hold in a steady state equilibrium. The assertion that we must cure unemployment with traditional fiscal policy is not supported by the facts and arises from a doctrinaire approach to the evidence.

The challenge for macroeconomic theory is to understand how fluctuations in asset markets are transmitted to aggregate demand and the fact that I am skeptical about the effectiveness of traditional fiscal policy does not mean that I think that the market should be left to correct itself. There are alternative policies we can try. But that is a story for another day.

...in most cases private spending falls significantly in response to an increase in government spending.Perhaps things are different at the lower bound? Nope! Ramey and Zubairy

...find no evidence that multipliers are different across states, whether defined by the amount of slack in the economy or whether interest rates are near the zero lower bound.I am not a right wing market touting Chicago card carrying loyalist. I want to find evidence to support effective policies to combat recessions. But I am tired of listening to diatribes arguing that there is incontrovertible evidence that fiscal policy is effective at the lower bound. There isn't.

Am I a Keynesian? I believe I am; but you can judge for yourself. My work explains (1). I am skeptical about (2) because the evidence suggests no stable connection between unemployment and inflation. In my view ANY combination of unemployment and inflation can hold in a steady state equilibrium. The assertion that we must cure unemployment with traditional fiscal policy is not supported by the facts and arises from a doctrinaire approach to the evidence.

The challenge for macroeconomic theory is to understand how fluctuations in asset markets are transmitted to aggregate demand and the fact that I am skeptical about the effectiveness of traditional fiscal policy does not mean that I think that the market should be left to correct itself. There are alternative policies we can try. But that is a story for another day.